Sandwiched in between Halloween and Christmas, Bonfire Night is easily one of the most anticipated nights of the year in the UK. Growing up in the 1980s, pre health and safety madness, my school put on a huge display of fireworks. Pumpkins lined the drive, we ran around with battery powered torches and scoffed hot baked potatoes wrapped in silver foil. The inevitable highlight of the night was huge roaring bonfire, that we couldn’t stand too near to because of the heat. It culminated in my headmaster, Mr A, tossing the guy on top of the roaring inferno and we’d watch it being slowly consumed by the flames.

Even as small children we were very aware of the traditional story of the Gunpower Plot. A group of rich Catholics including Guy Fawkes tried to blow up the Protestant King, James I and Parliament.

From an early age we were all taught the old rhyme:

What really happened and why?

The Plan

The aim of the plot was to kill King James I of England, aka James VI of Scotland, and most of the nobility of England, by using gunpowder to blow up the House of Lords during the State Opening of Parliament in 1605. After this, revolution would follow, with James’s daughter, the nine year old Princess Elizabeth being installed as a Catholic monarch. The country would then be rebuilt by the surviving Catholic nobles, who would guide England back into the arms of the papacy, the true faith.

In theory it was a simple plan. Led by the charismatic Robert Catesby, the conspirators: John and Christopher Wright; Robert and Thomas Wintour (Winter); Thomas Percy; Guido (Guy) Fawkes; Robert Keyes; Thomas Bates; John Grant; Ambrose Rookwood; Sir Everard Digby; and Francis Tresham would lease an undercroft (a cellar) directly below the House of Lords, where gunpowder would be stored. This would then be ignited when the House was in session.

What went wrong?

The plan started to go awry in August, when it was discovered that the gunpowder stored in the undercroft had decayed and had to be replaced. Furthermore, the opening of Parliament was delayed until the 5th of November because of the threat of plague in the warm summer months in the city. The plan had to be reworked.

In October, it was finally decided that Guy Fawkes would be the man to light the fuse, leaving him to try and escape across the River Thames.

The delay to the plot meant that slowly, many of the conspirators began to have second thoughts. Many of them had personal, or family connections to some of the Catholic nobles that would be attending the House of Lords that day. They expressed concern at what was going to happen to them.

On 26th of October, Lord Monteagle, the conspirator Tresham’s brother-in-law received a letter from a servant, who claimed to have been given it by a stranger. Monteagle ordered that the letter be read aloud to the assembled company.

‘My Lord, put of the love I bear to some of your friends, I have a care of preservation. Therefore I would advise you, as you tender your life, to decide some excuse to shift your attendance at this parliament; for God and man hath concurred to punish the wickedness of this time.’

It was not surprising that after such a public reading that the letter found it’s way to Robert Cecil, the Earl of Salisbury, the King’s right hand man. It was eventually shown to the King on 1st November. The King took action. On November 4th the undercroft was searched. The King’s men found a large pile of firewood there. They also met a serving man (Fawkes) who told them that the firewood belonged to his master, Thomas Percy, a known Catholic agitator. At the King’s insistence the search party returned to the undercroft to undertake a more efficient search. Hidden under the firewood they found 36 barrels of gunpowder. Fawkes, who was also found inside the undercroft was arrested and taken before the King.

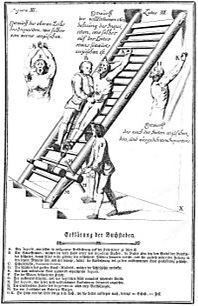

The conspirators fled as news of Fawkes’s arrest was spread across the London. The city’s gates were closed, as were the ports and the house of the Catholic Spanish ambassador, a protected place, was surrounded by an angry mob. Arrest warrants were issued for the conspirators. Fawkes faced his first interrogation, but would not give up the names of the plotters. In view of this; on 6th November the use of torture was authorised by Royal prerogative. Historians believe that Fawkes was subjected to the rack before he confessed late on 7th November.

In the meantime on 6th of November, the conspirators who had fled had made as far north as Warwick Castle where they resupplied their weapons. After contacting Catholic priests and trying, but failing to raise an army by rallying Catholics and recusants they found themselves holed up at Holbeche House. There, they resolved to make their last stand against the King’s men.

On 8th November, the Sheriff of Worcestershire laid siege to the house with 200 men. After a skirmish Grant, Morgan, Rockwood and Wintour were arrested. Catesby and Percy were killed.

Eventually Bates and Keys were captured. Digby was caught. Tresham was arrested. Those with links to the conspirators were imprisoned in the Tower of London. Whilst the nation sighed in relief at the deliverance of the King and Parliament.

The conspirators were interrogated by Sir Edward Coke. The threat of torture proved too much and many of the conspirators confessed.

On 26 January 1606, the surviving conspirators were charged with treason in Westminster Hall. The result of the trials was a foregone conclusion. Four days later the executions began. Four of the conspirators were dragged through the streets of London. Everard Digby was the first to face the executioner. His clothes were stripped to his shirt. He was hung in a noose, but quickly cut down. Whilst he was still fully conscious he was castrated, disembowelled, and quartered. This punishment was then enacted on the remaining three men. The following day four were hung, drawn and quartered at Westminster. Knowing what was to come Fawkes jumped from the gallows, breaking his neck in the drop. Even Catesby and Percy, who had died during the skirmish at Holbeche did not escape the King’s revenge. Their bodies were dug up and decapitated. Their heads were displayed on spikes outside the building they tried to blow up, the House of Lords.

The result of the plot

The case for tolerance towards Catholics and their rights for freedom of worship seemed very far away in 1605. The discovery of the plot led to greater anti-Catholic persecution. In the summer of 1606 legislation against recusancy was strengthened with the introduction of the Popish Recusants Act. This law expressly banned Catholics from entering the professions of medicine and law. It allowed magistrates to enter and search Catholic homes looking for weapons. It instated a new oath of allegiance, (which became know as the Oath of Obedience). One which required English Catholics to swear allegiance to James I over the Pope. It denied the power of the Pope to depose a monarch. It became an act of high treason to obey the Pope rather than the King. Recusants were required to receive the Eucharist, aka the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper at least once a year in a Church of England parish church. If they refused they faced a fine of £60, or the loss of two-thirds of their land. This effectively tied the English Catholic nobility to acceptance of James’s reign and his church. Surprisingly, James’s reign proved to be a lenient time for Catholics and few actually faced prosecution. Nonetheless the threat of persecution remained.

The plot was commemorated in church by sermons and the ringing of church bells. It became an important part of annual Protestant celebrations and embedded itself into the National and religious life of England.

On a wider scale, the Observance of 5th November act was passed, making it a legal requirement to commemorate the foiling of the plot. The act remained a part of British law until 1859. Even today, Bonfire Night remains one of the most popular nights in the British Calendar. It is widely celebrated, both at home and in public, with a plethora of organised displays taking place across the country.

Who Benefited? Cui bono?

Certainly not the Catholics. For many years, they were blamed for the Gunpowder Plot and this version of history was not questioned. Indeed, it was not until 1829 that Robert Peel passed the Catholic Emancipation Act and Catholics were once more welcomed back into Parliament and public offices.

Recently, historians have moved away from simply accepting that the Catholics were at fault and have begun to debunk the many myths surrouding the plot that were hitherto previously just accepted as fact.

Many historians believe that Gunpowder plot was all just a bit too convenient. It was too easy to foil the plot and point the finger at the Catholics. Antonia Fraser speculates that it was Cecil, the Earl of Salisbury who gained the most from the attempted regicide. She postulates that Cecil used Catesby as double agent and then made him the fall guy for the plot. Catesby was deliberately pursued and killed at Holbeche House, which prevented him from being able to name Cecil’s involvement in the plot, or testifying. To further muddy the waters we know remarkably little about Robert Catesby to be able to prove, or disprove this definitively.

Tantalisingly, Robert Catesby’s servant when he was dying, made statements asserting that Catesby and Cecil had met on three occasions in the lead up the Gunpowder Plot. Furthermore, the servant claimed that Thomas Percy was another agent of Cecil’s involved in ensuring the success of the plot.

The Motive

1605, was reasonably early in James I reign in England. His predecessor, Elizabeth I had died in 1603. She had relied on William and Robert Cecil to ensure the smooth running of the country. When she died it was Robert Cecil who had negotiated the accession of James, who descended from the Stuart line and had been barred from the succession, under the terms of Henry VIII’s Testament. James I was already the ruling King of Scotland when he inherited the throne from Elizabeth. He had his own ideas and his own way of doing things. James was remarkably tolerant of Catholicism. His mother, Mary Queen of Scots, had established herself as a Catholic martyr at her execution. One of the first things James did when he inherited the throne was to do away with the old Recusancy laws that Elizabeth had been forced to impose upon Catholics. Even worse, as far as Cecil was concerned was that he had been sidelined. James’s tolerance of Catholism was in his opinion dangerous for the realm, and because he was a committed Protestant, posed a threat to his own power. Religious toleration would weaken England and could not be permitted in any circumstances . Eventually he feared that the Catholics would demand more power.

Interestingly, it was the Monteagle letter that busted the plot wide open. This letter was conveniently read in front of an audience who could witness that the letter had been handed anonymously to a servant. The letter was taken immediately to Robert Cecil, rather than anyone else, who immediately ordered the search of Parliament and captured Fawkes.

Treasham who was almost certainly the author of the letter was locked in the Tower of London rather than face the interrogations and torture of Coke. He was later found dead in his cell. The official story is that he was poisoned, but who would had gained from his death and why? Who had access to him?

Whether you believe that the Gunpowder Plot was a Protestant plot, or Catholic conspiracy one thing is certain. The foiling of the plot permeated English identity. Whether consciously done, or not, it unified the English against a homegrown Catholic enemy and united the public in favour of the King. It built on the tradition of the Spanish Armada, 1588. In that being a good Englishman became synonymous with Protestantism. They knew who they were and who they were not, ensuring the continuation of anti-Catholic sentiment, to grow and fester in the British public for the next 200 years.